Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution

"I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the "obsolete" hand-loom weaver, the "utopian" artisan, and even the deluded . . . from the enormous condescension of posterity. Their crafts and traditions may have been dying. Their hostility to the new industrialism may have been backward-looking. Their communitarian ideals may have been fantasies. Their insurrectionary conspiracies may have been foolhardy. But they lived through these times of acute social disturbance, and we did not. Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience."

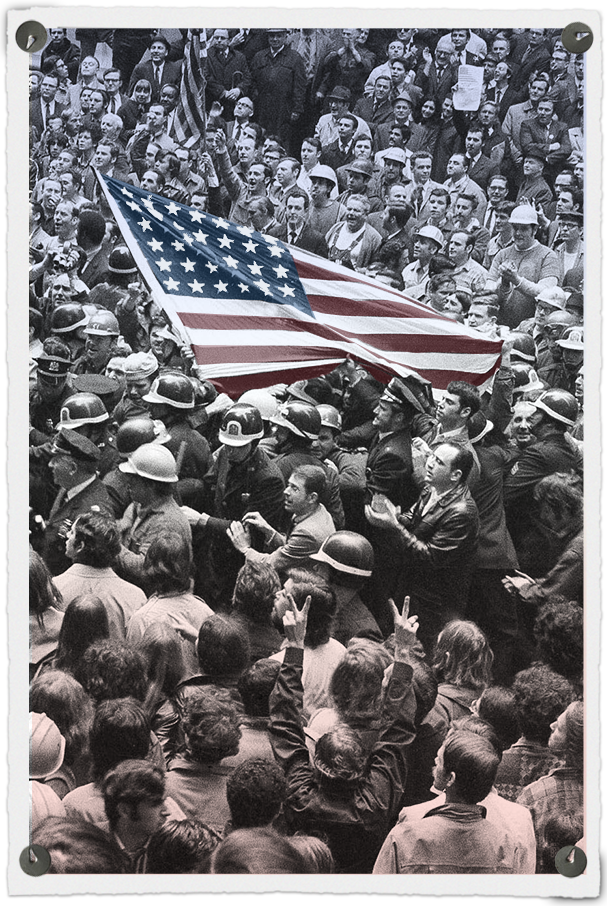

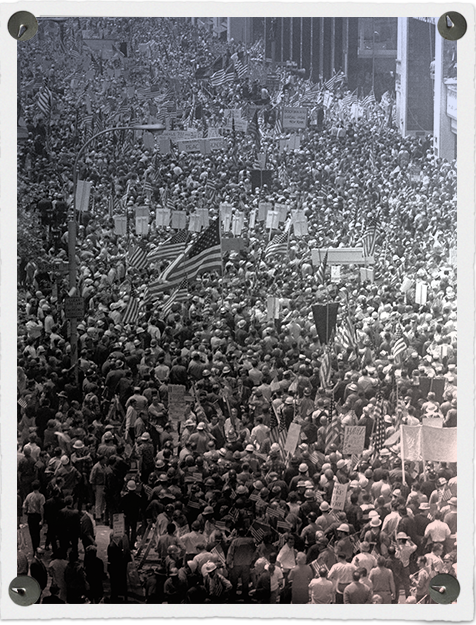

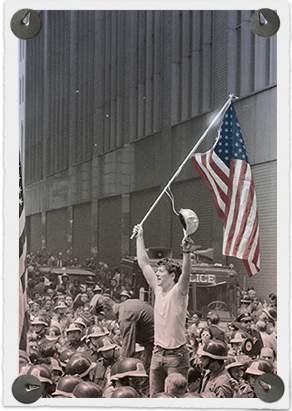

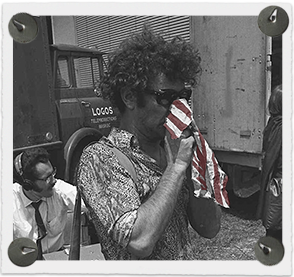

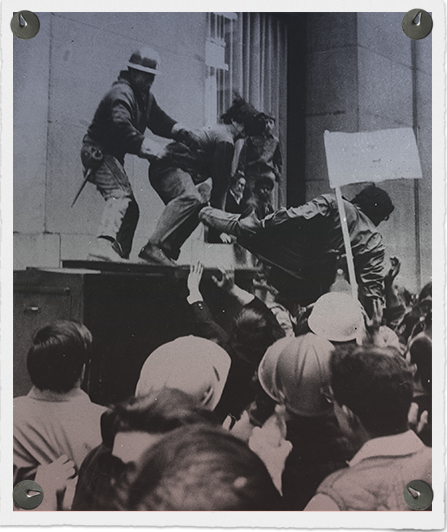

They arrived in waves, in colored hard hats and worn steel-toed boots, shouldering American flags, thundering, "U—S—A. All the

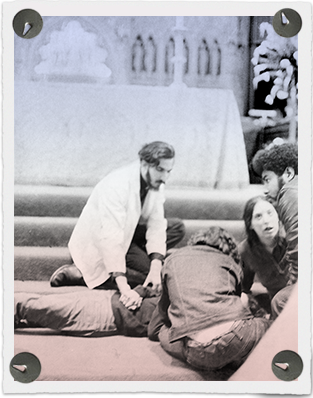

way," intent on confronting antiwar demonstrators on Wall Street. Police rushed to form a human chain and separate the two factions. Hippies chanted, "Peace now!" Hardhats shot back, "Love it or leave it!" The protestors pushed forward and shouted their opposition to the "fucking war." They expected it to be a matter of words. They had been told "the police are here to protect us." Then, in the same place where George Washington was inaugurated, the construction workers charged and the police did not protect them.

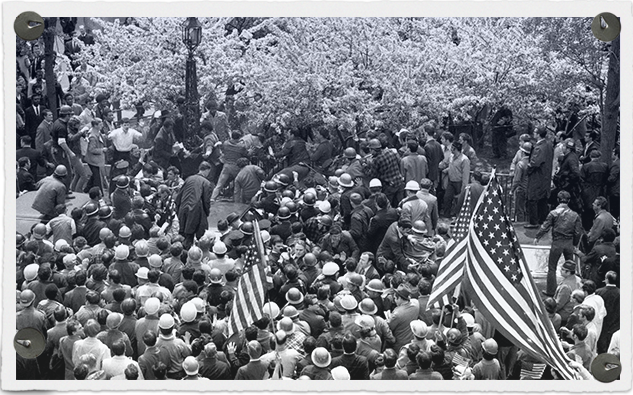

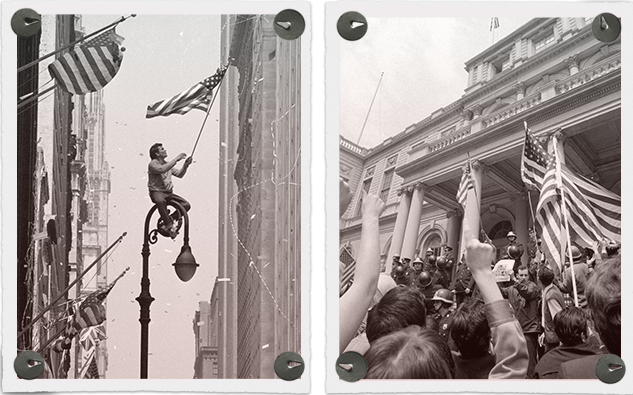

The hardhats plowed through thousands, swinging their fists wildly, fighting to raise American flags. Students tripped and screamed and flailed for escape. For hours, they ran for their lives "like a cattle stampede." Young people were pulled from melees by their hair. Others were found unconscious and prone in the dirty streets. By the time the police realized the scope of the riot, the mob was too large and the cops were too few. City Hall was now under siege.

Two liberalisms collided that day, presaging the long Democratic civil war ahead, and revealing a rupture expanding across the American landscape, a divide that had grown so vast it seemed unbridgeable by the time elites noticed. That is, unless one looked back to understand how it all began.

An earthquake only feels like an aberration. We know otherwise, of course. It's the consequence of vast plates that move with glacial time, mere millimeters a year, yet build mountains and carve oceans. Normally, these plates pass one another with friction so minimal it doesn't register in our lives. But sometimes too much subterranean stress amasses and the plates get stuck, frequently where the strain has long collected—that is, a fault line. Then the pressure rises. The force exceeds what bonds the plates together. Blocks of crust collide and some fall. The fault line ruptures and the land shakes.

"The Hardhat Riot, by David Paul Kuhn, vividly evokes . . . a blue-collar rampage whose effects still ripple, not the least of them being Donald Trump's improbable ascension to the presidency . . . this is a compelling narrative."

In 2016, the Democratic nominee performed worse with working-class whites than any other nominee, of either party, since the Second World War. Yet before that fateful campaign, we had arrived at a place where the party of the workingman relied most on the allegiance of educated whites, and the party of big business depended on working-class whites. Years later, even well-informed Americans still struggled to consider all Donald Trump exposed—the fragility of our norms, the degradation of blue-collar America, aloof elites, the corrosion of our common ground. What revealed that corrosion, and shook American life afterward, was not detached from history. It was the consequence of a tectonic break a half-century ago.

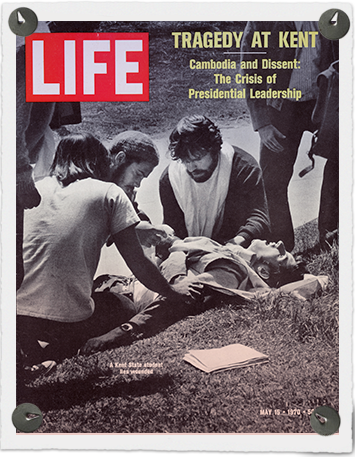

May 1970 was a tumultuous month in a tumultuous era. After Cambodia and Kent State, the antiwar movement revived and radicalized as never before. Even after Watergate, Richard Nixon recalled these weeks as some of the most traumatic of his presidency. His expansion of the war into Cambodia caused a cascade of events that brought much of the nation to the brink, and Nixon with it—until, as William Safire put it, the hardhats helped "turn the tide."

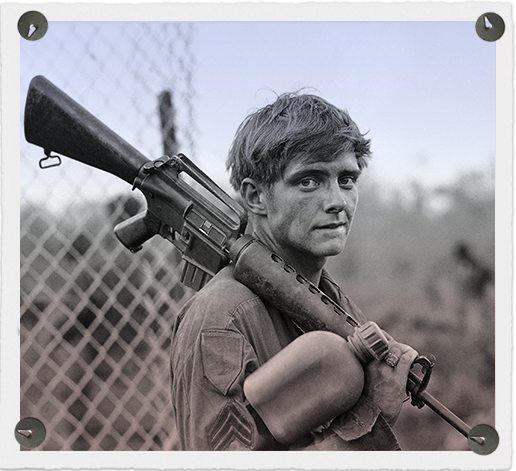

Those who raged most against the war were not only college students, they also tended to hail from suburban affluence. They were the educated youth who ushered in the counterculture, who believed in men by the name of Gene McCarthy, John Lindsay, and George McGovern. They were also a class apart from most soldiers over there. Most Vietnam veterans were blue-collar whites. They were usually boys of the lower middle class and poorer backgrounds. Vietnam, unlike any war since at least the Civil War, asked the most of those who came from less.

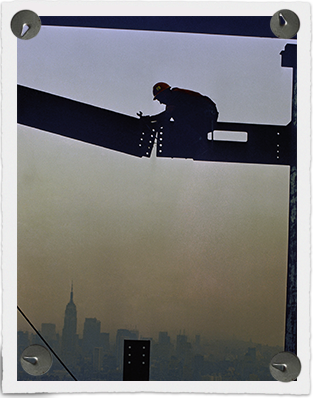

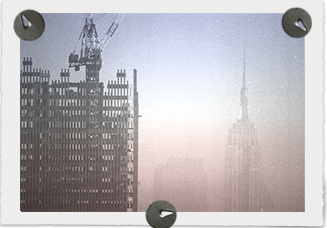

New York was still a blue-collar city at the dawn of the 1970s. The deindustrialization of America had hit it early and hard. The consequences for the city forecasted those for America. For a time, New York staved off the worst. There was a roaring national economy, a stock market bubble, a "Second Skyscraper Age" remaking downtown. Thousands of tradesmen and laborers crowded into Lower Manhattan for the work, including to build two colossal towers.

It was a cold rainy morning when hundreds descended those towers and other worksites between Battery Park and the Bowery. There was talk of it being their turn now, of reaching their "boiling point." Some solely wanted to "break heads."

It was the era when FDR's everyman first turned against the liberalism that once had championed him. When Richard Nixon, more than any other, moved the Republican Party from blue bloods to blue collars and wrote the strategic playbook for GOP campaigns thereafter. It was when the New Left won popular culture, then the Democratic Party, but lost blue-collar whites along the way. And that conflict never burned brighter and more brutal than during the Hardhat Riot, when two archetypes of liberalism clashed, and the Democratic Party proved one of its casualties.

The hardhats won the day but lost the long fight. Blue-collar whites' societal clout withered before their wages did, but that too was near. This book brings us back to when the middle class reached its apex in American life, and working-class whites began their long march to less. The Hardhat Riot, and what it inspired, was not the turning point in the story of America's conservative party winning the working class (a peculiar tale when seen beside other developed nations in the second half of the twentieth century). Few historic moments are without precedent. Few people change tides. But sometimes episodes capture an era and steer the current. Sometimes, the contemporary can best be understood by the lessons of history, including one story that shifted history.

We rarely recall the past linearly. Our memories feature the events that struck us, for good and for ill. This is a book, in part, about the issues and episodic dramas that drove the hardhats to the streets, these men who became stand-ins for Nixon's Silent Majority, in the same year that Time magazine named "Middle Americans" its person of the year.

This is also the story of a city, a mayor, a president, a people, and an era when the nation diverged—living different cultures, different wars, different economies, until the American experience became so fragmented that the singular became an anachronism. It was not even a year after Americans had landed on the moon. It was a time of big things. At the dawn of the seventies, however, those big things that had helped unite these states already felt like vestiges of a fading nation.

"In his engrossing, well-crafted, The Hardhat Riot ... [that's] deeply researched ... Kuhn argues persuasively that the riot sparked a vast national political shift driven by a widening divide between the working class and the educated elite that has led to the era of the Trump presidency.... Corrects some misperceptions ... Kuhn writes with empathy for both sides.... Kuhn's accounts of the violence are vivid and raw. . . . The author concludes with a sharp analysis of how the revolt of the White working class almost immediately reshaped American politics ... right up to the making of Donald Trump's political base."

It's unclear why the Hardhat Riot's story has gone untold until now. The thousands of pages of never-before-seen records, which served as the foundation of the riot's story, could have been accessed sooner by an industrious researcher. Histories of the era tend to note the riot as a flare of backlash, if they mention it at all. At the most contentious level, perhaps that stems from what all freshmen history students learn: that winners write history. We think of that axiom in terms of the wars between nations. But it also applies to cultural conflicts within nations.

There are other riots we associate with the era, whose stories have been told. The Detroit Riot, Attica, and Stonewall were fundamentally significant for what they symbolized. And, as Stonewall reminds us, their full meaning is not always recognized in their time. Yet the Hardhat Riot resonates with the significance of presidents by the name of Reagan and W. and Trump. Modern liberalism, and the innumerable books and films born of it, capably depict the "root causes" that shaped contemporary Democratic constituencies. Here is a book—not the book, just a book—that reaches back to Democrats' old constituency. This is a book about some of our history, of stories not yet fully told, that shaped American politics for more than a half-century after. Many of the seminal Vietnam marches of the era, such as the march on the Pentagon immortalized by Norman Mailer, had fewer attendees than the hardhats' largest rally, the "Workers' Woodstock" recounted in this book. Or maybe this story is only now being told for simpler reasons. Episodes of the past sometimes require the present. Or is it, rather, that a difficult present compels a better understanding of what made it?

The first day after the Hardhat Riot, it was front-page news and network evening news. But it faded into footnotes and anecdote thereafter. Perhaps, however, some early tremors' importance is only appreciable after the quake. And it's the aftermath—whether it has come to pass or has only just begun—that highlights the need to go back, back to the time when Manhattan sank as the World Trade Center rose, to when regular people had to answer for their convictions, and to a day that captured it all, when two liberalisms battled and the era's festering divisions first exploded on the streets of New York.

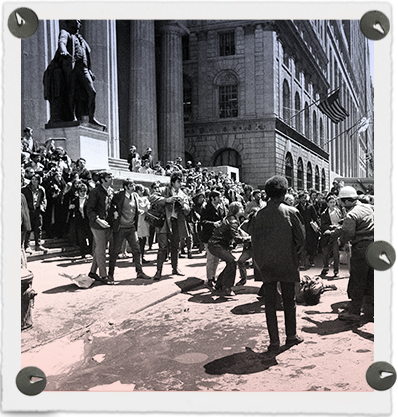

Protests had become common within the Financial District's main plaza, where Wall Street and Broad Street cross beneath the New

York Stock Exchange, the House of Morgan, the Bankers Trust tower, and Federal Hall, the site of the first US Congress and George Washington's inauguration. "Wall Street, like other streets across the nation, has been rent by antiwar protests," the Wall Street Journal fumed in an editorial that morning. It was one of those cold,wet mornings common to the city in early May, when the temperature feels closer to winter than summer. Still, by 7:30 students emerged from subway tunnels at Broadway and Wall Street, at Chase Manhattan Plaza, and weaved their way through commuters and an avenue crowded with yellow taxis that tinged neon in the rain, their tailpipe vapor drifting into Manhattan's interminable smog. The students gathered to the south, midblock. They had white armbands and held placards that read, now before it's never. More than 48,000 Americans were already lost to the war.

Demonstrators rotated two abreast before the Stock Exchange's marble colonnade. They were kids just south and north of twenty years, soft-looking, pale, shaggy. Boys, serious but subdued, with cherubic faces hidden behind overgrown beards. Girls with little makeup and often center-parted long hair. The clothing was loose, worn, wooly, velveteen. They wore bell-bottoms, antiwar buttons on big lapels, a lot of glasses. There was a girl in a baby blue poncho, her black hair halfway down her small back. A boy with circular eyeglasses and a faded green military coat, muttering, "Death is war." A girl in a striped serape. Her antiwar placard hung off her neck. A longhaired boy played his harmonica. At least one black boy, natural hair, dark clothes. A white boy with an afro.

Activists planned to "close down Wall Street today," once reinforcements arrived. For now, they were mellow. Many held their arms aloft, fingering peace signs, chanting, "Peace now!" Some sang "Dow Jones is falling down" to the tune of "London Bridge." A young man with an unkempt beard and beaked nose wore an inverted stainless-steel pot on his head. Still, antipathy accompanied the sparse lightheartedness. At one point, two businessmen in beige raincoats hurried by the picketers. A young protestor heckled: "Hey, how's the war profiting? Pretty good this week, huh?"

A student leader looked "fearful," police reported. He had heard construction workers planned to attack them. He reminded the cops that he had phoned them twice last night. The students would learn later that there had been other warnings.

About seventy-five policemen were assigned to the area for today's rally. Deputy Chief Inspector Valentine Pfaffmann told subordinates to "be alert" for clashes between hardhats and hippies.

It was Friday, May 8, 1970. Four days earlier, at Kent State in Ohio, four student protestors had been shot dead. One of the deceased hailed from a New York City suburb.

The antiwar movement had dragged on for years. Still, the body bags came home. Still, young people were drafted. Still, powerful men told America, We're winning. Still, the Vietnam War slogged on—and more boys died in a faraway land for a stalemate. Yet protestors believed Kent State was a turning point. That it clarified the stakes, that it was life or death for them too. That Americans would surely now champion their cause. That the war could finally end.

"[An] outstanding new book . . . through dogged research . . . combining eyewitness reports with his own gifted storytelling to craft a riveting narrative. In our current intellectual climate, which seems to prize tendentiousness, it is rare to find such a clear-eyed and non-polemical work of history."

Mayor John Lindsay believed that too. He was certain that the antiwar movement's opportunity was his own. Lindsay had closed the public schools for the day to encourage New Yorkers to "reflect solemnly on the numbing events at Kent State" and the "fate of America," giving more than a million students the day off. The Roman Catholic schools, heavily blue-collar and ethnic, remained open. Advisors had urged Lindsay to also lower American flags citywide. "Who could complain?" mayoral aide Sid Davidoff thought. "Nonviolent kids were shot by National Guardsmen!"

In recent days, however, there had been scattered confrontations south of City Hall. The antiwar movement's resurgence had riled local workmen. Thousands of construction workers were downtown. The city was experiencing its skyscraper renaissance. At one location, near Wall Street, hardhats were erecting the tallest towers in the world—the World Trade Center.

Meanwhile, by half past eight, as Mayor Lindsay played tennis uptown and protestors swelled to five hundred downtown, a workman phoned the police. He said hardhats "are out for blood today."

© Copyright 2020 by David Paul Kuhn. Reprinted from The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution. All rights reserved.

Photographer credits ordered from the top, left to right, for each page